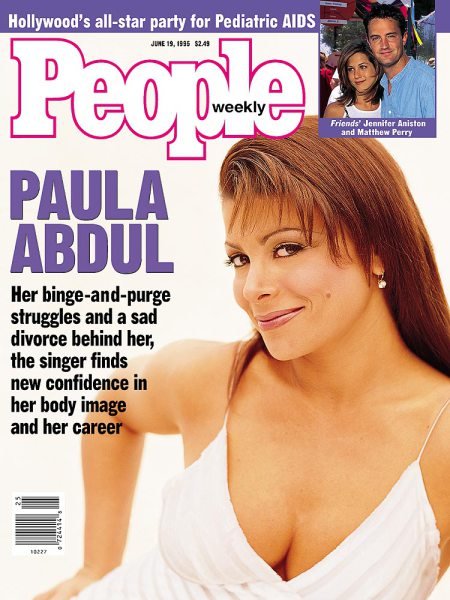

Paula's Battle with Bulimia [People Mag]

Jun 19th, 1995

Paula's Battle with Bulemia

Source: People Weekly, June 19, 1995

Author: Karen S. Schneider

Abstract: Singer Paula Abdul received treatment for an eating disorder in 1994, ended her marriage to Emilio Estevez and has just released her third album, 'Head Over Heels.' Abdul's bulimia dates back to her teenage years, and she is proud of overcoming it.

Welcome to the palace of Paula Abdul, Pop princess. Here, just outside the peach-colored walls of her $3.2 million Spanish-style mansion above Beverly Hills, is a pond where rare Japanese fish flit back and forth beneath a gurgling fountain.

Nearby, a winding pool leads to a sun-filled kitchen. And the airy dining room is fragrant with the smell of fresh-cut roses and tulips-- and, Abdul suddenly notices, dog pee. "Oh, Punky," she moans, scooping up her 1-year old Chihuahua. "What am I going to do with you?" Then she stops, smiles and says, "Please don't tell anyone my dog doesn't have bladder control."

In fact, Abdul doesn't give a hoot if the world knows her puppy's secret. "Secrecy," she says, laughing. "What is that?" For Abdul, 32, secrecy has at times been a way of sustaining pain.

Six years have passed since the former L.A. Laker Girl burst onto the music scene with Forever Your Girl, a debut album that sold 12 million copies, produced four chart-topping singles and turned her into a star overnight.

Since then, Abdul has experienced other highs: an Emmy for choreographing The Tracey Ullman Show, a Grammy for her Opposites Attract video, her 1992 marriage to actor Emilio Estevez. She has also endured humiliation and sorrow. In 1991 her record company was sued by a backup singer who claimed that her voice had been used to enhance Abdul's vocals; in 1994 her marriage to Estevez ended in divorce.

None of that, however, affected Abdul as deeply as the secret she has, until now, kept from almost everyone: her 15-year battle with bulimia.

"I'd starve myself, then binge, then purge," says the 5'2", 105-lb. singer, wincing at the memory. "Whether I was sticking my head in the toilet or exercising for hours a day, I was spitting out the food -- and the feelings."

Today, she says, her eating and exercise problems are behind her. A month-long stay at the Laureate Psychiatric Clinic for eating disorders in Tulsa last year helped give her the confidence to work out problems and fears with friends, family members and music-business colleagues rather than with her refrigerator.

Head Over Heels, her just-released third album, is, she says, her most honest and personal project to date. "I took all the stuff I was afraid to face," says Abdul, "and put it in my music."

What happened after Abdul hit her peak is something she is still struggling to understand. "The confidence I had when I was just plain anonymous Paula eroded," she says. "Suddenly being Paula Abdul was not a very comfortable place to be."

In truth, it never was. For Abdul, who was raised in Van Nuys, Calif., the tough times started when she was 7 and her sense of home and family was shaken by divorce.

Her father, Harry, now 62, the owner of a water-bottling company, moved more than 200 miles away to Northern California. Her mother, Lorraine, a onetime classical pianist, moved with Paula and her sister Wendy, now 39 and a homemaker, to a condo in the San Fernando Valley community of North Hollywood. "I didn't understand it," says Abdul of the split. "My mother did a great job of being there, and I saw my dad on weekends. But it was hard."

As a way of coping with the changes, Abdul lost herself in old musicals on TV and dreamed of being the next Ginger Rogers. "She'd watch Gene Kelly and be totally enthralled," says her father. "She was always a ham, and there was always a crowd around her. The bigger the crowd, the harder she'd work."

When she was 8, Abdul started taking ballet lessons and comparing herself to other girls. "My friends were tall and thin," she says. "I was short and round." It didn't help that her instructor used Abdul as an example in a discussion on anatomical variations. "She pointed out that my body was different," says Abdul. "I had such a feeling of shame. From then on I never felt right."

When she was 15, she received a scholarship to a dance camp near Palm Springs. There, in addition to training in ballet and modern dance, she learned how many of her long-legged teachers stayed so lithe. "They were all throwing up their food," says Abdul.

Shocked, she phoned her mother. "That's not normal," Lorraine told her. "Don't do that." Abdul didn't -- for a couple of years. As a student at Van Nuys High School, she reached her full height -- all of 62 inches -- and weight: between 100 and 110 lbs. When she hit the higher end, she ate only salads and drank only diet soda. "A pound or two on a shorter person," she has said, "is very different from what it is on a taller person." Her parents assured her she looked fine. It didn't matter; when she looked in the mirror, she saw someone fat.

One night when she was 16, after eating Mexican food with her cheer leading squad, she went home and did what so many of her friends had long done: she stuck her finger down her throat. "No one thought it was bad," says Abdul. "Once I tried it, I felt it was an amazing way to control my weight."

By the time she enrolled at Cal State Northridge in 1981 with the intention of becoming a sportscaster, she was deep in the frenzy of a bulimic eating disorder. Either she binged and purged or spent up to 4 hours a day sweating off the calories she had consumed.

Her disorder, though, never got in the way of her drive. During her freshman year at Cal State, Abdul tried out for the Lakers cheerleading team. The judges selected her from a pool of some 700, and within three weeks she was the squad's choreographer. She quit school six months later, but her career took flight. Abdul's high-energy, street-funk style delighted fans -- including the Jackson family, who saw her at a game and hired the 20-year-old to choreograph a video for their 1984 Victory album.

Soon she gave up her Lakers gig for a life of creating dance routines for Janet Jackson, George Michael, Aretha Franklin, even Tom Hanks in the 1988 movie Big. "My biggest claim to fame," the actor told Abdul after she mapped out the famous dance number he performed on a giant keyboard, "is that you once choreographed me."

In 1987 she used $35,000 in savings to put together a demo of herself singing. Though her voice was untrained, her moves were magnificent, and in an MTV-driven business, she proved highly marketable.

Virgin Records signed her the same year; by 1989 her singles "Straight Up," "Forever Your Girl" and "Cold Hearted" had all reached No. 1 on the pop charts. "It was a magical experience," says Abdul.

It was also more pressure than she had bargained for. "I remember, at a rehearsal for a TV show, I couldn't stay focused," Abdul says. "I felt nervous and out of control, and all I could think about was food. Food numbed the fear and anxiety. I'd eat, then run to the bathroom."

Abdul put on a stoic face when, in April 1991, Forever Your Girl backup singer Yvette Marine filed a $1 million lawsuit against Virgin Records, claiming producers had combined her voice with Abdul's without giving credit. Though not named in the suit, Abdul took the charge as a personal affront. Both she and Virgin vehemently denied any wrongdoing. "I do not profess to be any Aretha Franklin . . . but that is my voice," Abdul told the Los Angeles Times.

Privately, though, she was deeply embarrassed. For her, the mere suggestion of fraud tainted the release of Spellbound -- which nevertheless went on to sell 6 million copies. "People in every city asked, `Are you singing live? Is that really you?' " she remembers.

But not everything was bleak. Suddenly, Abdul was seeing a man whom, until the spring of 1991, she had known mostly by telephone: Emilio Estevez, then 29. Before him, Abdul's only other serious romance had been with Full House star John Stamos, whom she dated for seven months in 1990. Most of her relationships ended, as Abdul told the Chicago Tribune, for the same old reason: "I'm very career oriented. . . . The guys I was with didn't understand that."

Estevez seemed different. The actor first called her when she was dating Stamos, just to tell her he was a fan. Every couple of months, he would pick up the phone to touch base. Then, when she was performing in Manhattan before her world tour in 1991, she got a message on her phone at the Plaza Hotel.

Estevez was staying there too, and he wanted to meet for dinner. "After that he would send flowers or letters to every city I was in," says Abdul. "We would have phone conversations and visit every few weekends. We thought everything was perfect."

Some six months after their first date, Abdul flew to see Estevez in Minneapolis, where he was filming The Mighty Ducks, and found herself in his hotel staring at an engagement ring. "He got down on his knee and said, `I've been in love with you for a long time. I don't want to live my life without you,' " recalls Abdul. "I just melted."

The two were married in a Santa Monica courtroom in 1992. At first their life together was as charmed as their courtship. They spent weekdays in her hilltop home, weekends in his Malibu Beach house, took hikes in the Santa Monica Mountains and went to movies together. Abdul opened up to her husband about her deepest fears and her most private problems. A member of Overeaters Anonymous since 1989, Abdul attended meetings three times a week with her husband's support. "He wanted what was best for me," she says.

Estevez was also an emotional support when the Marine suit came to trial in 1993. Although she was not required to be at the trial, Abdul, outraged, sat in the front row every day for a month. The jury deliberated for less than an hour before returning a verdict in favor of Virgin and, in effect, Abdul.

It was when Abdul wanted to get on with her life, she says, that she realized there was a problem in her marriage: children. Before they married, says Abdul, "I let [Emilio] know that I was very interested in having children." Estevez, already the father of two -- Taylor, 11, and Paloma, 9 -- from a previous relationship with model Carey Salley, initially agreed, she says, but later changed his mind. "It was very hard for him to admit that he couldn't handle having kids again," she says. "It was heartbreaking for us both."

After many tear-filled but, Abdul says, civilized talks, the couple filed for divorce in May 1994. Abdul took the split hard. She couldn't concentrate, and for a while she couldn't eat. Then she couldn't not eat. "I was so sad, I just needed to be filled up," she says. "It was like I was trying to fill this big empty hole." Though she stopped herself from throwing up, Abdul knew she was headed for trouble. "I felt totally not together," she says. "I was sad, hurt and frustrated, leaving the recording studio in tears. I knew I needed help."

Two months later, without telling even her family, Abdul checked into the Laureate clinic on the advice of her therapist. Her attempt to deal privately with her problems ended on the third day when she was ambushed by paparazzi and became front-page tabloid news. "I had to call my parents and tell them what was happening," she says. It turned out to be a blessing for them all. "She's my baby," says Lorraine. "You don't ever want to see your kids having trouble. But I was so proud of her."

Her father, too, offered support. When he visited the clinic, he and his daughter confronted for the first time many past issues, starting with the divorce. They even had one unexpected bonding experience. While buying cappuccino together at an outdoor mall in Tulsa, Paula's Chihuahua ran into the street and was killed by a passing car. Abdul was devastated. "It was the first time I'd seen my daughter that emotional," says Harry. They wept together as they walked back to the clinic. There an exhausted Paula went to her room to take a nap. A few minutes later, Harry says, she called out to him, "Daddy, can you come lie down next to me?" He did, and, he says, "we shared a moment we wished we had shared 20 years earlier."

One loving encounter does not, of course, remake a life. Curled up on a velvet sofa in her living room, Abdul says the lessons she took away from the clinic are tools, not cures. "There are three things I commit to on a daily basis," she says. "Exercising for an hour a day, tops. Never skipping meals. And accepting the size and shape I was born with." Keeping those commitments is not always easy. "There have been many times when I sat and clenched my hands and said, `Okay, Paula, you're feeling really upset about what you just ate and it's not healthy. Get over it.' "

Everyone who knows her believes that she will. Yet for all the support she receives, Abdul realizes her health -- and happiness -- are in her own hands. "My life took a difficult turn, and I'm proud to say I survived it," she says. She hopes the future will bring more musical success and someday a husband and children. "I do want to meet a special person and get married again," says Abdul, currently unattached. "I believe I'm well-deserving of that." But whatever comes, she says, she is determined to face it with the strength she feels now. "I have no doubt I'll keep up my commitment to myself. I feel too good. And this is no bull," she adds. "This is my life."